Friday, November 27, 2009

Mohit Sen--some moments from history

Excerpts from

A Traveller And The Road—

The Journey Of An Indian Communist

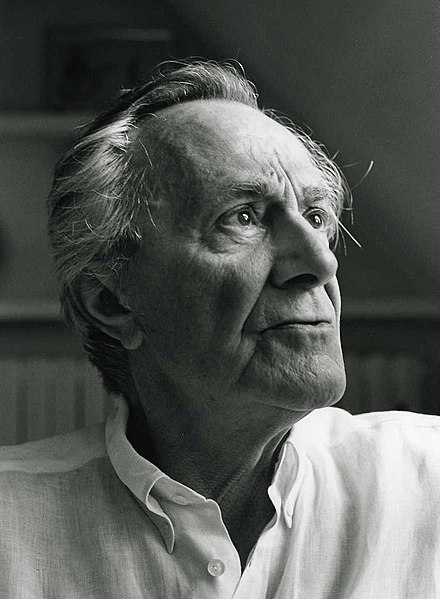

By Mohit Sen

"CPI's first blunder"

We were all Communists at a difficult time for the Communist Party. This was the period in the party's history when it opposed the Quit India movement, when it characterised the war as a people's war, participating in which was the best way for India to fight for its freedom. In theory, this didn't mean that the fight for our own freedom should be postponed so that the freedom of the Soviet Union could be preserved and for which the latter's alliance with British Imperialism was indispensable. In theory, the people's war line could be presented as a line of struggle for freedom superior to that of the Quit India movement.... In practice, it was the Quit India movement that was opposed. Subhas Chandra Bose was shown in cartoons as the pet dog of the Japanese, Jayaprakash, Aruna Asaf Ali and others were assailed as being the fifth column of the Japanese.... Bose's strategy of uniting with the enemy of our enemy was not just criticised but his patriotism itself questioned and assailed.... By the mid-1950s the CPI, however, came to the conclusion that its people's war line was erroneous and its abuse of Subhas Chandra Bose, Jayaprakash and other leaders was thoroughly wrong. As for the Soviet Union needing the CPI's support, Stalin is reported to have told the CPI delegation in 1950 that his country could have done without it and the CPI should have looked after itself. There is no doubt, however, that the CPI did what it did because of its belief that priority had to be given to support to the Soviet Union for the sake of Communism and Indian freedom even if it meant swimming against the national current.

"Gandhi blessed armed brigade"

Gandhi's presence in Calcutta and his fast did help to control passions. But with all due reverence, I would like to add that it did not do as much as official mythology makes out. The killers and their supporters had tired after it became clear that it was a drawn battle and that the new national secular state would not hesitate to act against the rioters and killers irrespective of their community.... Many stories have been told of armed gangs laying down their weapons before Gandhi. Professor Nirmal Kumar Bose, one of the pioneering anthropologists of our country, was his personal secretary at the time of the Calcutta killings. He later compiled a selection of the Mahatma's writings that still remains indispensable reading for those who wish to understand the great man. We met in 1969 at the Gandhi Centenary Seminar organised by the Institute of Advanced Studies in Simla. In the course of his address to the seminar, he told the story of a group of armed youth who came to where Mahatma Gandhi was staying to seek his blessings not by laying down arms but for using them against the mobs of looters, rapists and killers no matter which community they belonged to. They were all Hindus. Professor Bose was pleading with them to allow Gandhi to rest and not give him more pain than what he was already suffering when the great man himself came out to ask what the matter was. On being told what the youth wanted, he startled Professor Bose by blessing the young men and asking them to be as true to their vow as he was trying to be to his.

"Communist sympathies with China during war"

An influential section of the CPI leadership headed by Sundarayya did not accept that the Chinese Party was wrong. Sundarayya came armed with maps and archival material to prove that the territorial claims of China had a valid basis. He, of course, also harped on the theme that the Chinese Communists would never commit aggression while the bourgeois Indian government could do so to curry favour with the imperialists. Whatever be the consequences, the CPI as a Communist Party should stand with the Chinese Communists as this was its proletarian internationalist duty.In any event there was no question of lining up behind Nehru who headed a reactionary government that the CPI had always opposed and was pledged to overthrow. There should be no surrender to revisionist bourgeois nationalism as represented by Dange. He was supported among others by B.T. Ranadive, M. Basavapunnaiah, Promode Dasgupta, Harkishen Singh Surjeet, C.H. Kanaran and some others.

"And after"

...In the meantime, the press conference had begun and E.M.S. was asked whether he thought the Chinese had committed aggression. He said the Chinese had entered territory they thought was theirs and hence there was no question of aggression as far as they were concerned. At the same time, the Indians were defending territory they considered theirs and so they were not committing aggression either. Just then Dange walked in and sarcastically asked, 'And what is your opinion about the territory in question?' Even as E.M.S. fumbled for a reply, Dange stated that the Chinese had attacked India, occupied Indian territory and that the Communists supported Nehru's call to the nation to defend itself and repel the Chinese forces. He said the Chinese Communists had violated all the norms of proletarian internationalism, acted chauvinistically and broken its pledge to the world Communist movement that it would never cross the McMahon Line. His statement created a sensation but it was much more than that. The CPI had at long last taken a stand in support of the nation. The disastrous error of opposing the 1942 Quit India struggle on the ground that the defence of the Soviet Union had to be given prior and paramount importance was compensated for to a considerable extent. It's not that Communists were, or are not, patriotic. They have fought, suffered and sacrificed for the people of India and would do so again. But they often separated the people from the nation and even pitted the former against the latter.... Nehru argued at some length about the failure of the Left, especially the Communists, to properly understand India and to speak in a language that would be understood by the common people. By language he meant that which was in tune with the traditions and idiom of the people. This came in the way of their progress. Of course, he said, this did not apply to everybody of the Left, including the Communists, but was largely true. It also did not mean that the Left and the Communists had not made significant contributions to the national movement....

"When Nehru died CPI didn't care"

When Nehru died, I was in Hyderabad. Walking through the streets in different parts of the city, I could sense the spontaneous and tangible grief of the people. There was also a sense of bewilderment, of not knowing how exactly to express this grief and what to do about it. Even then I remember being shocked and saddened at the lack of feeling among the CPI leaders.... They had gathered to discuss the statement that the party should issue on the occasion. In the middle of the discussion, it was decided that what should be done was to leave the matter to the central leadership. And that was all. This was the attitude towards one of the greatest leaders of modern India and a person who had been a good friend not only of many Communist leaders but of the Communist movement as well. It was dogmatism and alienation from national feeling at its worst.

"Sanjay didn't run her life but..."

The person who stood by her (Mrs Gandhi) most firmly and called upon her to rise to the occasion on behalf of the nation was Sanjay Gandhi. He did much that was reprehensible and his instincts and outlook were not democratic and even fascistic. But he was an ardent nationalist, secularist and a firm believer in action.He also knew that his mother remaining in power was indispensable for India. His positive role at that crucial moment cannot be underestimated..... What was extraordinary was the latitude that Indira Gandhi gave him. Part of it can be explained by his strong attachment to her and the unfailing resoluteness that he had displayed at the point of extreme political and personal crisis for her just prior to the imposition of the Emergency. There was, however, something more than that. It is not true that he ran her life and credence should never have been given to the stories that he slapped her and abused her and that she was afraid of him. She pulled him up when necessary and took her own decisions as always. She trusted him, however, to the point of a kind of blind faith and refused to believe most of the negative reports about him that reached her. There was, additionally, a crowd of sycophants who only sang his praises and gave her false and exaggerated reports about how popular he was with the poor. The reality was that he was contemptuous of those who made up the so-called higher and middle classes from which most of the politicians, civilians and media persons came. He preferred the company not of the poor but the lumpens and the nouveau riche who jumped to his every command. He enjoyed humiliating those whom he could bully, notable among whom was Khushwant Singh but he was not the solitary example. Those who resisted him, he ruthlessly sought to destroy but did not always succeed...because of Indira Gandhi coming in the way.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Monday, November 23, 2009

Reflections on October Revolution and Crisis in Communist Movement Today - Mohit Sen

These excerpts are taken from Mohit Sen's Autobiography " Traveller and the Road ".

Though the birth of the communist movement took place in 1847-48 when Marx read out the Communist Manifesto, it would not be unfair to date its birth from the victory of the Russian Revolution on November 7, 1917. The news of its victory was sent ‘To All! To All! To All!’ Since then, despite defeats, it swept across the world as no other movement in the twentieth century. Its victory in Russia and its former colonies, the defeat of Nazism, the triumph in China, Yugoslavia, Cuba and Vietnam as well as its strong presence in Italy, France, South Africa, Brazil as well as in our country are facts that cannot be erased from history, that is, the memory of mankind. It was not only a question of geographical expansion. Some of the greatest masters of culture in science, literature, cinema, dance, theatre and the arts in the twentieth century became Communists or friends of communism.

In our country many among the great masters of culture were drawn towards communism and even more the Soviet Union. Satyajit Ray was among them. He told me that Soviet cinema had inspired him and also “the inspiration behind that inspiration”.

How did this happen? Before examining the reasons for this, it needs to be stated that communism’s triumph was essentially that of Lenin and Leninism. He was a superb tactician undoubtedly but not only that. Lenin was an unsurpassed Marxist theoretician enriching all the three components of Marx’s legacy—dialectical and historical materialism, political economy and scientific socialism. Yet, if one were to pick out his greatest and most original contribution to Marxism and revolutionary thought and practice in general, it would be his concept of the vanguard party. He first set out this concept in What Is To Be Done? It is not democratic centralism nor discipline that are essential to this concept. What is essential is the relation between spontaneity and consciousness and between the intelligentsia and the working class. The Party is conceived as the indispensable link between the science of socialism and the movement and struggle of the working class that creates socialist consciousness. Such consciousness has to be brought to the working class from outside the sphere of the life and struggle of that class but it has to be brought to that class and brought by the intelligentsia that has grasped the science of socialism.

Few adequately understood Lenin’s theory of the Party. Among the exceptions was Antonio Gramsci whose Modern Prince embodies this concept in all its complexity. Such a party existed only as long as Lenin lived and is born and reborn only when it begins its journey in country after country. The Italian Communist Party led by Togliatti and Berlinguer was an exception. In a different way, for a shorter period along with errors, so was the CPI in the 1934-47 period when P.C. Joshi was its General Secretary, that is, in the earliest years of my adherence to the Communist Party...

It is significant that while Lenin and Leninism triumphed when they were most themselves, the triumphs associated with Stalin occurred when those actually leading such parties disobeyed him and returned to Lenin, to put it figuratively. This applies to the defeat of fascism, the victory of the Chinese, Yugoslav, Vietnamese and the spectacular advance of the Communist Parties in some countries, especially Italy and France.

The building of the power of the Soviet Union and extensive social welfare was an astonishing feat accomplished as he desired. The price in terms of lives, destruction of much of the Russian heritage accompanied by Russification of the non-Russian nations, miscalculations, leading to waste and distortions in the economy on an extensive scale, was far too heavy and much of it unnecessary. The loss caused by the dissociation of communism from democracy and freedom can never be counted. In the end, socialism was not constructed in the Soviet Union….

¨

I would now like to return to the theme of the spectacular success of the communist movement till the middle of the seventh decade of the twentieth century.

In the first place, there was the objective contradiction embedded in capitalism, that is, between the continually increasing socialisation of the process of production and the individual appropriation of the surplus resulting from this process. The appropriation of the surplus could be and was subject to increasing social control after the Great Crash of 1922-1931 and the form of its appropriation by individuals could be and was altered. Yet, to this day, that contradiction remains and capitalism as the final system based on the private ownership of the main social means of production cannot rid itself of it.

The communist movement presented progra-mmatically and in the practice of its protest and assault an alternative to capitalism. It possessed formidable strength in its combination of Marx and Lenin—one more a thinker and the other more a practitioner but each being both. In addition to being an alternative, it successfully presented itself as an advance on capitalism. It was not a retreat, not a return to any supposed golden age of the past. Moreover, communism was both in terms of theory as well as practice a carry forward of the already existing modes of thought and action.

The twentieth century was for communism its century. In this century, the central contradiction mentioned above expressed itself not so much through the capitalist-worker conflict as through the contradiction between feudalism and the peasantry and that between national liberation and imperialism. This was graphically expressed in the change of the central slogan from ‘Workers of the world, unite!’ to ‘Workers and oppressed peoples of the world, unite!’

The success of the communist movement, it should not be overlooked, was the greatest in countries with no democratic traditions and institutions. Communists succeeded most where they confronted power more than hegemony, where competition from other parties also opposed to the oppressor’s system was weak and where the revolution took the form of a war of movement culminating in a lightening final destruction of the enemy’s citadel. Gramsci’s strategy had elements of Leninism but was essentially an alternative to it. This strategy, it is not enough realised, depended on its success, on the building of a united front not of classes directly but in the mediated form of already existing parties. It required for its success a comprehensive hegemony and not just in the political sphere. It required cultural hegemony understood in the broadest sense. It required a party capable of hegemony. Such a party had to be a collective individual and the ‘Modern Prince’—a concept that Gramsci developed brilliantly on the basis of Machiavelli’s classic text….

Stalin’s memorable oration at Lenin’s funeral was literally soul-stirring. It was, unfortunately, highly sectarian—‘we Communists are men of a special mould, we are made of a special stuff’. There were, of course, no lack of statements by Stalin, Mao and other Communist leaders insisting on the Party maintaining the closest links with the masses, serving them and learning from them. Yet, the theory and the functioning of Communist Parties did push them from bring vanguard parties to becoming elitist parties substituting for the masses. They tended to become something like religious orders—the Society of Jesus comes immediately to mind. It feels good to be a member of such a party so long as you do not disagree with the Party line and are either a member of the leadership or liked by the leaders. The pinch comes and somewhat more than just a pinch when you disagree, are pushed into dissidence and eventually to being thrown out. It was Trotsky who said that you can never be right against the Party and ended up as an exile. The titles of Deutscher’s great triology on Trotsky sum it all up—the prophet armed, the prophet disarmed, the prophet in exile. It required immense stamina and courage to have worked on in conditions of increasing isolation and irrelevance.

¨

Apart from Lenin’s greatest contribution to history—his theory and practice of the Party—turning into a handicap to the making of history there were gaps in communist theory that led to the setback and crisis in which it finds itself today.

The failure to understand democracy is one such gap. Revolutionary and liberal democracy had their limitations but they raised humanity and its history to a new level. The Communists grasped only the limitations of civil libertarian democracy. They pointed out quite correctly that at a certain moment in history democracy served the interests of the bourgeosie. It did not always promote equality nor fraternity and did not come in the way of exploitation and oppression. In many ways, it served to disguise the predatory character of the bourgeoisie. It also created illusions that by participating in the liberal democratic system, the emancipation of the exploited and oppressed could be achieved. Such participation was also to be confined to the electoral sphere and of increasing the economic well-being of the working people. It was to be evolution without the punctuation of breaks from an existing equilibrium. The communist movement ignored the leap in history accomplished by the emergence and advance of democracy and the fact that it was both a value in itself and cherished by the oppressed as a necessity in the struggle for their empowerment. The disregard and even destruction of civil libertarian democracy became a part of its outlook and practice.

Another such gap was the failure to appreciate, much less to promote, the scientific-technological revolution that stormed ahead in the twentieth century, transforming all components of society and that brushed aside all that came in its way. The Soviet Union made spectacular scientific-technological advance but Stalinist dogmatism and anti-democratism not only limited that advance but at times opposed and struggled against it. The crassest example was, of course, in the sphere of genetics. In the development of the technology of warfare, it lagged behind especially as far as computers were concerned but partially made up for it by enormous extra expenditure that eventually crippled its economy and led to its destruction. Essentially, the Communists did not believe that the scientific-technological revolution could precede the victory of socialism on a global scale.

Another gap was with regard to what constituted the working class and what its role was in the progress of history of socialism. The dominant understanding was to restrict the concept of the working class as being applicable to the industrial workers directly engaged in material production. It was assumed that these workers would, by the very fact of their objective location, not only come over to the socialist ideology and the Communist Party but lead it. This just did not happen anywhere except for a few exhilarating initial years of the Russian Revolution. The sweeping advance of the communist movement could by no means be attributed to the working class that practically nowhere became a class for itself, far from becoming the universal class envisaged by Marx….

¨

Still another gap was the failure on the part of the Communists to correctly evaluate nationalism. Lenin understood the strength and the positive nature of nationalism. This was most clearly expressed in his polemics with Rosa Luxemburg and later M.N. Roy. He was also quite aware of the menace of nationalism degenerating into chauvinism. Still, in theory, the nature of nationalism as an arena of class struggle and not necessarily the expression of the interests and the ideology of the bourgeoisie was not appreciated. In practice, either internationalism was counterpoised to nationalism or it was allowed to flourish as chauvinism.

In India, as elsewhere, the Communists were patriots and champions of the working people of the country. But they were not nationalists. They did not know India. In my own case, I became a Communist and worked as a Communist for decades before I accepted India. I was not an exception. Mao Zedong was wrong in wanting to Sinicise Marxism and to bring into being Chinese communism. The correct effort would have been to be Communist and Chinese. Ho Chi Minh achieved this. So did Joshi and Dange. But they were exceptions. Of course nationalism could turn ugly and did. But so could communism itself and it did.

The correct understanding of nationalism—its imperative, dangers and potentialities—was needed by the communist movement not only in the colonial and post-colonial countries but also in the imperialist countries. It was no accident that in the anti-fascist struggle the Communists were defeated, among other reasons, because the Nazis and other fascists took over the national traditions and sentiments of the people. Dimitrov was severely critical of the national nihilism of many Communist Parties.

The Communist approach to religion has also contributed to its failures and setbacks.

Religion as an ideology and as an institution could not be dismissed as tended to be done by the Communists as only an opiate of the masses. Historically, it played a progressive role in the emergence of civilisation in different parts of the world and acted as a unifier and inspiration of the tribal peoples. It embodied lofty ideals, high moral principles and the complexity of life. It still does so. At the same time, it inevitably tended towards inflexible dogmatism, was an impediment in the way of scientific enquiry and was the handmaiden of the exploiters and oppressors of the people. It was the ideological form of murderous conflicts though also of the popular desire for unification and liberation. Some of the great liberators of the people were deeply religious. Gandhi was one of such leaders, though not the only one.

Most important of all for those like the Communists who were seeking to lead the masses, was the deep attachment of vast numbers of the latter to religion. These included many of those who were supporters and even some who were members of Communist Parties. It should not be forgotten that if the Communist Parties tended to be vehement opponents of organised religion, the latter more than repaid the compliment. The historic compromise proposed and attempted by the Italian Communists vis-à-vis the Catholic Church was needed by both and it was the latter which, in the end, refused to go ahead with the experiment.

What the Communists, generally speaking, lacked was an appreciation of religion as one of the forms of man’s appreciation of his limits and the yearning to transcend these, to overcome mortality through time—only through time is time conquered. Joseph Needham’s attempt to integrate the sense of the holy with the communist movement flickered out.

¨

In India, the communist movement advanced but did not triumph, it passed through serious setbacks but was not defeated. Even now in its different formations the communist movement in India is, I dare say, more recognisably and significantly Communist than almost anywhere else in the world. This was an expression of the madhyam marg that has characterised those who helped India to make its history. The Communists of India could have done more for themselves and their country had they understood that they could not have accomplished much on their own. They should have been more a ‘part of the main’. The Congress did not take over the space that rightly should have belonged to the Communists. In fact, it was the space also of the Communists who did not accept this reality. It was, and remains, a pity. For too long we imitated the Russians, and the Chinese because, after all, we had not succeeded and they had. This was an important reason for our failure. I have lived this combination of struggle, advance, failure and continuation for half-a-century and tried to set it out in the preceding chapters and therefore will not reiterate. We should not imitate others, nor just try to be different. We should, at least now, look more closely at where we are and do what our conscience and understanding dictate. We have to change, but we do not need to give up our history and our identity.

A final world about our deficiencies. This applies to the communist movement worldwide and not only to India. Indeed, this is a problem, for all scientists. It is the overwhelming of method of theory. What the method enabled us to reach and build into a systematised form tends to become an obstacle to the further use of the method. Theory becomes unquestioned and unquestionable dogma. Received wisdom becomes a barrier to going beyond to newer realms of knowledge.

Human fallibility is all too often due more to prejudice and jealousy than to lack of understanding. Extraneous considerations come in the way of doing what you know you should. Brecht has written, as mentioned earlier, ‘Unhappy the nation that needs heroes’. I would add, ‘tragic the movement that cannot have the heroes it needs’!…

….We perhaps attempted too much but that is what the times demanded and proclaimed. We would have made more mistakes and achieved less had we not attempted to do the impossible. Out of such folly is loveliness born and the world remade even if by others. We pass on our message of historical impudence. My only regret is not that we were not wiser but that morally we were not better. We had too much of personal ambition and realised too little that to be good one had to know the pains of others—the true Vaishnavite ‘peer pariye jaane re’. It was not difficult to understand but extremely difficult to give priority to….

…Communists we have been of different kinds. There will be other kinds in the future but Communists there will be. More open than we were, less arrogant and going along with many others who will not be Communists but whose aims, though differently expressed, will not be all that different from and not antagonistic to what Marx wished for humanity. He predicted fulfilment without insisting that a particular party was needed for it. History would do it in its own way. It is enough that we were given the chance to be a part of its greatest forward movement.

Ajoy Ghosh-A rare breed but forgotten Indian communist-by Sankar Ray

A rare breed but forgotten Indian communist

Ajoy Ghosh

by Sankar Ray

If you take a random sample from amongst the card-carrying members of Communist Party of India and ask them to write four paragraphs on Ajoy Ghosh, after whom is named the national headquarters of the party, overwhelming majority will not be able to write more than four sentences. But Boris Ponomaryov, alternate member of the now-vanished Communist Party of Soviet Union for about two decades and a historian on the Communist International(Comintern) , described Ghosh as among the handful of ‘sterling leaders’ of Comintern era along with Ho Chi-Minh, Dolores Ibaruri, ‘La pasionaria’ of the Spanish Republican struggle of the 1930s, French communist stalwart Maurice Thorez, Antonio Gramsci’s comrade-in-arms Palmiro Togliatti, British scholar-communist Rajani Palme Dutt and the like. None among the stalwarts of undivided CPI is in the Ponomaryov-list. N K Krishnan, a polit bureau member of undivided CPI in the end-1940s, wrote that Ajoy Ghosh was the only CPI leader who disagreed with CPI’s stand on Quit India Movement ( he opposed the support to the colonial government while supporting the concept of ‘people’s war’ in the global concept of anti-fascist struggle) and the sectarian line of 1948 ( Ranadive thesis). You can’t blame the rank and file of CPI for being unaware of one who was a one man barricade against those who actively indulged in the process of splitting the party much before the official fissure at the Tenali Plenum on 8-11 July 1964. After the split, CPI biggies themselves seldom highlighted Ghosh who ultimately expressed his preference for the CPI’s programme of National Democracy (ND) to CPI(M)’s Peoples Democracy (PD). Was it because Ghosh’s contemptuous chagrin against factionalism and propensity to friendly inner-party ideological study to keep the party intact was not liked by rabid factionalists who were on both the sides ? However, as a ritual, Ajoy Bhavan mandarins will observe the birth centenary of Ghosh who was born on 22 February 1909 ( for Ajoy Bhavan bosses, he was born on 20 February 1909, but the late S G Sardesai, a CPI central secretariat in the 1970s, who inspired Ghosh to gravitate towards Marxism in the very early 1930s, accepted the former date). Its leaders often talk of reunification of communist parties. If they are genuine defenders of reunification, they could organize a national seminar. Excepting those who are obsessed with a cavalier-fashion historiography in judging the history of communism in India, it is generally believed that the CPI had three most outstanding general secretaries – P C Joshi, Ajoy Ghosh and E M S Namboodiripad. Dr Ranen Sen whose birth centenary is due on 23 September this year and the only one who remained a member of CPI central committee from its inception in 1933 up to the split in 1964 told this writer ( Dr Sen’s personal secretary during his twilight years) quite often. “ Comrade Ajoy was head and shoulder above all the general secretaries before or after the party split. But for his premature death on 13 January 1962, the party might not have been split.” Ghosh was imprisoned by the British rulers for having been involved in the Lahore Conspiracy Case as a junior comrade of Bhagat Singh who influenced him profoundly. He too opposed both Hindu and Muslim communalism although agreeing that the Hindu variant was a much bigger threat to the democratic polity. In his last- published article in the CPI weekly New Age - ‘For the Unity of our Motherland’ – he warned against Hindu communalism that permeated into India’s ‘ social and political life’ and ‘is even more dangerous’ . But he castigated other communal variants too. “When I say communal parties, I have in mind all communal parties, whether Hindu, Muslim or Sikh”. He added, “Any opportunistic association or alliance would be a positive disservice to the cause of national integration”. How Ghosh took on the split-syndrome in zealously factional leaders at the Sixth CPI Congress ( Vijaywada, April 1961) is a lesson for those who look forward to reunification of communist parties in India. Both the draft party programmes – ND and PD – were circulated. Along side the draft political resolution, placed by Ghosh with support from EMS who was virtually next to him in the central secretariat, the alternate draft , jointly placed by P Sundarayya, M Basavapunnaiah, Jyoti Basu, H K Surjeet, Promode Dasgupta, Bhupesh Gupta and others among 21 national council members were circulated. Ghosh, EMS and most of the delegates agreed that instead of adoption of a single programme and a PS ( the last jamboree of undivided CPI), there be a debate after the Congress. But split syndrome remained manifest. The Left-leaning group – PD- liners resorted to pressure tactics a day before the penultimate day. One by one, they withdrew their names from the proposed panel for the new NC. Actually, they wanted more Left-adherents in the NC. Ghosh smelt a provocation for a split and proposed to increase the number of NC members to accommodate them, in consultation with Mikhail Suslov, head of the delegation from the CP of Soviet Union proposed that the size of the NC be enlarged to accommodate more. He emulated Lenin who in his Letter to the Congress – known also as his Testament Lenin suggested that the size of central committee be enlarged from 50 to 100 to save the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party from being split by Stalin and Trotsky factions. Defying his serious illness ,Ghosh delivered his historic speech New Situation and Our Tasks – the only document adopted at the Congress. Unfortunately, it is said that Ghosh saved the party through a patch-up.

source-Australia.to-World News

Saturday, November 21, 2009

MARX’S “NEW HUMANISM” AND THE DIALECTICS OF WOMEN’S LIBERATION IN PRIMITIVE AND MODERN SOCIETIES Raya Dunayevskaya

MARX’S “NEW HUMANISM” AND THE DIALECTICS OF WOMEN’S LIBERATION IN PRIMITIVE AND MODERN SOCIETIES

Raya Dunayevskaya

I

In the year of the Marx centenary, we are finally able to focus on the transcription of Marx’s last writings — the Ethnological Notebooks of Karl Marx (transcribed and edited, with an introduction, by Lawrence Krader, 1972). They allow us to look at Marx’s Marxism as a totality and see for ourselves the wide gulf that separates Marx’s concept of that fundamental Man/Woman relationship (whether that be when Marx first broke from bourgeois society, or as seen in his last writings) from Engels’ view of what he called “the world historic defeat of the female sex” as he articulated it in his Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State as if that were Marx’s view, both on the “Woman Question” and on “primitive communism.” To this day, the dominance of that erroneous, fantastic view of Marx and Engels as one1 (consistently perpetuated by the so-called socialist states) has by no means been limited to Engelsianisms on women’s liberation. The aim of the Russian theoreticians, it would appear, has been to put blinders on non-Marxist as well as Marxist academics regarding the last decade of Marx’s life when he experienced new moments in his theoretic perception as he studied new empirical data of pre-capitalist societies in works by Morgan, Kovalevsky, Phear, Maine, Lubbock. In Marx’s excerpts and comments on these works, as well as in his correspondence during this period, it was clear that Marx was working out new paths to revolution, not, as some current sociological studies2 would have us believe, by scuttling his own life’s work of analyzing capitalism’s development in Western Europe, much less abbrogat- ing his discovery of a whole new continent of thought and revolution which he called a “new Humanism.” Rather, Marx was rounding out forty years of his thought on human development and its struggles for freedom which he called “history and its process,” “revolution in permanence.”

download full here

source -praxis international

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Thursday, November 5, 2009

Jean-François Lyotard (1924—1998) and the theory on Postmodernism

French post-structuralist philosopher, best known for his highly influential formulation of postmodernism in The Postmodern Condition. Despite its popularity, however, this book is in fact one of his more minor works. Lyotard’s writings cover a large range of topics in philosophy, politics, and aesthetics, and experiment with a wide variety of styles. His works can be roughly divided into three categories: early writings on phenomenology, politics, and the critique of structuralism, the intermediate libidinal philosophy, and later work on postmodernism and the “differend.” The majority of his work, however, is unified by a consistent view that reality consists of singular events which cannot be represented accurately by rational theory. For Lyotard, this fact has a deep political import, since politics claims to be based on accurate representations of reality. Lyotard’s philosophy exhibits many of the major themes common to post-structuralist and postmodernist thought. He calls into question the powers of reason, asserts the importance of nonrational forces such as sensations and emotions, rejects humanism and the traditional philosophical notion of the human being as the central subject of knowledge, champions heterogeneity and difference, and suggests that the understanding of society in terms of “progress” has been made obsolete by the scientific, technological, political and cultural changes of the late twentieth century. Lyotard deals with these common themes in a highly original way, and his work exceeds many popular conceptions of postmodernism in its depth, imagination, and rigor. His thought remains pivotal in contemporary debates surrounding philosophy, politics, social theory, cultural studies, art and aesthetics.

Lyotard’s theory on Postmodernism

By tllabello

Postmodernism is defined according to Lyotard as taking the rules of modernism and using them as guidelines for postmodernism. Lyotard states in his “What is Postmodernism?” piece, “…it must be clear that it is our business not to supply reality but to invent allusions to the conceivable which cannot be presented” (81). Also postmodernism has the writer refer to something the author is alluding to in their stories.

Most of Lyotard’s theory can be summed with one quotation which states, “A postmodern artist or writer is in the position of a philosopher: the text he writes, the work he produces are not in principle by preestablished rules, and they cannot be judged according to a determining judgment, by applying familar categories to the text or the work. Those rules and categories are what the work of art are looking for. the artist and the writer, then, are working without rules in order to fomulate the rules of what will have done” (81). This shows the difference between modernism and postmodernism as that modernism looks for form in writing and have rules where postmodernism use different forms in their writing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)